- Home

- Aonghas Crowe

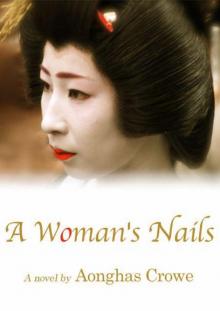

A Woman's Nails

A Woman's Nails Read online

A Woman’s Nails

By

Aonghas Crowe

A Woman’s Nails

Aonghas Crowe

Published by

Three Black Crows Publishing

Portland, OR 97225

This novel is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover design: Kuroko

Copyright © 2010 Aonghas Crowe

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

1

ABAZURÉ

1

Sometimes I can't shake the feeling, the sinking feeling that my life is little more than the punch line of a very bad joke. Someday when I can’t take it anymore, when I finally cry “uncle”, I know in my heart of hearts that God will be waiting for me. The bastard will give me a friendly jab to the shoulder and say, “Sorry, Peador, I was just feckin’ with you.”

Looking at my reflection of the darkened window of the subway car, I can see I’m a mess. After what the Almighty Prankster has put me through this morning, it’s hardly surprising.

As the train pulls into the station, my gut rumbles. Nature has been calling for the past half hour and I really should pop right into a toilet and relieve myself, but, there isn’t a minute to spare.

Abazuré[1] couldn’t have been more explicit about being on time. “You cannot be late,” she said at the end of last week’s interview. “Not even once.”

I had arrived twenty minutes late for it. What can I say for myself? I’m human and, well, stuff happens.

“I do not tolerate sloppiness or tardiness,” she said. “Is that understood?”

“It is.”

“Your boss told me that you were often late.”

The bastard!

I admitted that I might have been late a few times over the course of the year. But often? No, no, no. That was an exaggeration. “Did my boss inform you that he had me travelling all over Kitakyûshû in the rain, sleet, and snow? Yes, I may have been a few minutes late every now and then, but I always overcompensated by staying . . . “

“Well, I won’t tolerate you being late even a few minutes,” she said. “Is that clear, Peador?”

“Crystal.”

“Can you promise me that you won’t be late?”

“I can,” I answered wearily.

“Then I’d like you to come again next week. And be there by nine sharp.”

“Nine o’clock sharp,” I said, writing the time down in my day planner. “I will be there. You can count on me.”

And yet here I am, and it’s two minutes of nine when the train pulls into the station. I’m one missed step from getting sacked even before I’ve been officially hired.

My intestines do a somersault as I step onto the platform. I really should head straight for the restroom, but time’s not on my side.

If only I hadn’t taken the slow train. If only I had made the connection. If only . . .

Twenty-six years old and my life is already a litany of regrets.

Climbing up out of the subway station, my gut calms somewhat, giving me a reprieve. It’s the first bit of luck I’ve had all morning and so I quicken my pace, but not too fast. Heaven forbid I jump-start my bowels into peristalsis.

A few minutes later and short-winded, I stand before the foot of the stairs that lead to my next place of employment: The American School. After catching my breath, I climb the steps and introduce myself to a dour young woman sitting behind the counter. She says that Abazuré-sensei hasn’t arrived yet and, gesturing toward the next room, tells me in to take a seat and wait.

Plopping down on a shit-brown vinyl sofa in the lobby, I thank my lucky stars that I managed to get here before the president of the school.

The American School is a bit larger than the dismal little eikaiwa[2] I've been slaving away at for the last twelve months, but no less bleak. Like a dozen other private English schools in the city, many of which I've had the “pleasure” to visit for interviews before Abazuré finally called me back, there are the usual weathered stencils on the window declaring it to be an “English Conversation School”. There are classes for children and adults. Students, a sign states, may enroll at any time.

There are chalkboards instead of the more common white boards. In the largest of the school’s four classrooms small desks are arranged in a circle. The walls are decorated with the kinds of cheap posters you find at a teaching supply store in the States, and photos cut out of magazines. The lobby has been furnished with secondhand furniture. The sofa I’m sitting was, I imagine, once in Abazuré’s own living room.

It is, in short, an uninspiring place. If the schedule weren't so ridiculously easy--only two or three classes a day compared to the five or six that have been teaching--I might have taken up employment at Yeehaw! English School, instead.

Being paid more to work less, that’s what this gig amounts to. As intractable as the dreariness hanging in the school's air is, that is still a song I can dance to. Better still, I'll have a boss who seems to know what she's doing, rather than the moron who clutches at straws just to keep from going bankrupt every month.

Even if the expiration date of my visa weren't bearing down on me, I tell myself, I would still leap at Abazuré's offer.

Considering how miserable my first year in Japan has been--after twelve months I've emerged heart-broken, humiliated, physically and emotionally exhausted, not to mention broke--you'd think I’d be ready to return to the States like everyone else I know is. Blame it on misfiring synapses, if you like, but it is precisely because the year's been so patently awful, that I sit here on a shit-brown vinyl sofa and think with muted optimism: Things can only get better. Things can only get better. Things can only get better.

It’s a congregation of one, of course, that I’ve been preaching to. No one else will listen. Every gaijin I know is going back to his or her home country, including my closest friend in Japan, Ben, the only person who can honestly say that he's had a fulfilling year.

None of my expat friends mince their words. You must be a masochist to even consider staying another year, they say. Why subjugate yourself to another twelve months of what will surely be more of the same bullshit and hassles, they ask. Like a proselyte whose faith has been challenged, I defend the choice and remind them that I will not only be teaching less but will be living in Fukuoka City rather than godforsaken Kitakyûshû.

I'm not very convincing, though. How do you expect me to be when I can't even win myself over to my way of thinking?

No, the truth behind my willingness to remain in Japan is an obstinate unwillingness to let go of the thin hope that the woman I love might find it within herself to come back to me.

Fifteen minutes pass and still no Abazuré.

So much for the importance of being punctual . . .

I’ve been feeling like crap lately, really awful. And today my chest aches from the congestion, my nose dribbles nonstop. Every time I breathe in, the fluid in my lungs rattles like a hookah. And, if that weren’t enough, my stomach has started to act up again. The coffee I had earlier seems to have gone right through me.

Just as I'm about to stand up and inquire about the restrooms, Abazuré arrives. The four-foot-eight powerhouse smiles widely and bellows out a sunny greeting, then disappears into the office. I'd love disappear myself into the restroom, but figure it's best to wait, in spite of m

y stomach doing flip-flops.

Abazuré gives the girl in the office a big “Ohayô” after which the two chat in hushed voices. With the restroom beckoning, I'm tempted to interrupt but then Abazuré emerges. The broad smile she was wearing when she arrived is now gone.

She directs me to a smaller classroom where we sit across from each other at an old dining room table. She looks down at the document before her, hard nails tapping at the surface of the table. The woman is fuming about something and I haven't got the courage to ask what about. She looks up from the document, and stares at me through her steel-rimmed glasses. For a woman of such small stature, she comes off as formidable, intimidating, and downright frightening.

She inhales slowly, deeply before speaking. I inhale slowly, shallowly so as to not shock my bowels. I've begun to percolate and want nothing more of this world and this woman before me to be excused. Nature has stopped calling; it’s now shouting, imploring me. The way Abazuré is looking at me, however, tells me there's nothing I can do as my insides churn but try to squeeze my butt-cheeks together.

"In our conversation last week," she begins, "I made it very clear that you were not to be late . . . "

"Y-yes, I know."

"Yes, you know . . . “ She glares at me over the tops of her spectacles. “But, you were late today, weren't you?"

Jesus Christ, that bitch in the office went and told her I was late.

"Yes, but only . . . "

Oh mother of God help me! My bowels have started doing the rumba.

“I have a right mind to tear this contract up and find someone else. It wouldn’t be hard, after all. There are more than enough people out there looking for work.”

And then, Abazuré actually picks up the contract and rips it in half.

What the fuck?

2

I woke up shortly after dawn and stuck out my kitchen window to check the weather. The cold air bit my cheeks and my breath clouded before me, but the slag heap to the west of the working class neighborhood that had been my home for a year was bathed in the glow of the rising sun. With the sky promising to clear up, it made sense to dress lightly, to endure the chill in the morning rather than sweat through what promised to be a lovely spring day.

After a shower, I dressed in a light suit and tie, and hurried out the door. As I was walking away from my apartment, appreciating the sweet smell of magnolias in my neighbor’s garden, Ben rounded the corner. He had the habit of jogging in the morning and steam was billowing from his head and shoulders; the front of his gray University of Wisconsin sweatshirt was black with sweat.

“Leaving already?” he asked.

“Yeah, I have to be there by nine this morning to sign the contract.”

“You might wanna bring an umbrella,” Ben suggested. “TV said it’s gonna rain. Niwaka ame. I think it means a sudden shower, or something like that.”

“Yeah, right,” I replied looking up at the sky. As much as I liked Ben and had come to depend heavily on his advice over the past year, his comprehension of the Japanese language just could not be trusted. The fact alone that the man still hadn’t realized that his Christian name, Ben, meant excrement in Japanese was enough to peck away at the urgency of taking an umbrella. “Besides,” I said, “I’ll miss the bus if I go back now.”

I should have listened to him. No sooner had I started up the hill towards the bus stop than the wind picked up, the sky darkened, and heavens opened up, the rain falling in torrents.

Niwaka ame. I’ve learned a new word.

Halfway between the bus stop and my apartment, I was paralyzed with indecision and getting wetter by the second. Do I run back and fetch an umbrella only to risk missing the bus, or do I hightail it to the bus stop, and try to find some shelter under the awning of the rice shop until the bus comes?

The rain had already soaked my head; icy rivulets were now running down my neck and back. Umbrella or no umbrella, I was going to get drenched, so I forged ahead, up the hill. As I neared the bus stop, the approaching bus plowed through a cascade of water flowing along the curb, sending a wall of water towards me. I tried to leap out of the way, but wasn’t fast enough. By the time the bus stopped, my pants were sopping wet from the knees down, my feet sloshed around in their loafers.

Looking like something that cat drug in, I boarded the bus and took a seat next to a floor heater. I rolled my pants up and tried in vain to dry my feet.

As the damp settled into my clothes, a chill rattled up my spine and the chest cold that had been pestering me for a month started pestering me some more. I managed to suppress the first sneeze. And the next. But the third one was doozie. It developed up deep inside me and, as it gained strength, I rifled through my pockets, frantically looking for a handkerchief.

For the love of God, how could I forget a handkerchief?

The sneeze came, carrying with it the generous contents of my nasal passages, and deposited it all into my cupped hands.

Opening the window, I stuck my hands out into the rain to try to rinse the snot off. Then, taking the silk pocket square out of my breast pocket, I dried my hands.

By the time the bus arrived at the train station, the niwaka ame had already passed. The sky, however, was still overcast and the air much colder than it had been when I left my apartment. Looking around at the sleepy mob standing on the platform, I could see that everyone, but me, was wearing a heavy winter coat over his suit or a scarf bundled around his neck. Spring may have been evident in the buds of the sakura trees and in the frenetic activity of birds, but the wind barreling down the platform was all winter.

A “local train” rolled into the platform. I knew I’d be cutting it close if I took it, as it would stop at every blessed station from now to Hakata, but the limited express train wasn’t scheduled to show up for another fifteen minutes. I’d surely catch myself a death of a cold if I waited on the platform, exposed to the cold wind. I hopped on, figuring I could always transfer to one of the express trains several stations down.

It was lovely inside the train. Unlike the express in which salarymen and office ladies are usually packed in like cattle off to slaughter, there were only a handful of students dozing off or staring blankly out the windows. It was an older model of train, and the thinly padded pews-like cubicles offered a modicum of privacy.

When the train jerked into motion, the heaters below the seat kicked on. I removed my shoes and socks and tried to warm my poor little blue toes.

Warm air bathed my calves, climbed up my legs, enveloping my knees, and drifted toward my face. Before I knew it, the heat and relaxing sway of the train as it made its easy way to Fukuoka lulled me to sleep.

When I woke up the train was completely empty. Looking out the window, I couldn’t recognize the station.

"Shûten des’. Shûten," came over the PA system.

Last stop? You gotta be kidding. How long have I been asleep?

I pulled my warm but slightly damp socks over my feet, slipped on my soggy loafers and scrambled out of the train. The platform clock showed eight twenty-five, giving me thirty-five minutes.

But where the hell am I?

I cornered one of the clean-cut uniformed station employees on the platform told him where I wanted to go and was directed with a white-gloved hand towards the stairs.

I dashed down them and on to the turnstiles where I asked another employee for directions.

"Sutorayto. Sutorayto," he said.

“Straight. Gotcha!”

I hurried out of the train station and back into the cold, continuing “sutorayto“ as directed where I was supposed to eventually come upon a subway station.

The sun I’d been counting on when I left my apartment was now hidden behind a menacing layer of black clouds and a chilly breeze was blowing in off of the bay. Before long, I was shivering like a maniac and my cold was acting up: my chest ached and my nose ran like a leaky faucet.

At a vending machine I bought two cans of Georgia coffee, which I tucked

them under my armpits for warmth. Pressing on, I walked, hunched over, hot cans of coffee under my armpits, until I came to the subway station. I now had twenty minutes to travel six stops and walk from the station to the school; meaning I'd just make it by nine.

I purchased a ticket and as I was about to pass through the gate, a gust of warm air blew up from the bowels of the station, followed by the horn announcing the train's approach. I scampered down the first flight of stairs to a broad landing where I was offered two options: left or right. The signs were all in goddamn Chinese characters, no English to be found.

Although I'd been studying the language for a year, had even been scribbling the pictograms down in a notebook, I couldn't recognize any of them on the sign.

I turned to a man and blurted out the name of my destination, but he scurried away without answering me. A young woman avoided me altogether. Then a soft-spoken middle-aged woman approached and asked in fluent English where I was going.

“The Ôhori Park station. Ôhori Kôen.”

“Oh, Ôhori Kôen. Yes, yes, it's very nice this time of year.” The words trickled slowly out. I could hear the swoosh of the train doors opening, the click of heels on tile as the passengers got off.

“Yes, yes, I know. Which . . .”

“In a week or so, the cherry blossoms will be at their most beautiful . . .”

“Yes, I, I'm aware of that. Which platform do I . . .?”

“Oh, yes, the subway's a very convenient . . .”

“Oh, for the love of God, lady. Left or right?”

“I'm sorry? Left or right? I don't understa . . .”

“Which platform?” I said pointing towards the stairwells. I could have strangled the dimwit.

“Oooh, I see, I see. Platform Two, of course. I'll show . . .”

“No, you won't. I'm in a hurry. Bye.”

A Woman's Nails

A Woman's Nails