- Home

- Aonghas Crowe

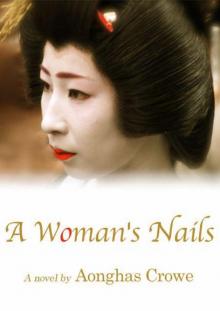

A Woman's Nails Page 19

A Woman's Nails Read online

Page 19

“Tatami? Odd name.”

“An appropriately odd name for an odd girl.”

The waitress comes with Shinobu's “lady's setto” and my Caesar sarada. The girl serving us is a real doll. She asks if we need anything else and I’m thinking yes, your name and number and that charming smile of yours in my life.

“So?” Shinobu presses me.

“Huh?”

“Tatami?”

“Ah, right! Boy, where to begin? All I wanted was to be friends with the girl.” I say as I attempt to relate to Shinobu the exacerbating tale of a relationship sown in the fertile soil of misunderstanding.

“It’s not always easy for men and women to be friends,” Shinobu cautions. “It’s especially difficult for someone like your Tatami. I mean, if she’s from as good a family as you say, it’s impossible. People would think . . .”

“Shinobu, I don’t care what people think.”

“I know you don’t, but Japanese do. Anyone who sees the two of you together will naturally assume you’re a couple. And, anyone who knows anything about her family is going to conclude that you intend to marry her.”

“Perish the thought,” I say, but what Shinobu is telling me makes sense. It explains why Tatami always frets and worries.

“Tell me. You honestly aren’t attracted to her?”

“Not at all.”

“No?”

“No. I mean, it’s not as if she's a dog.”

“A dog?”

“Ugly.”

“Heh? But, dogs are so cute.”

“Whatever. Like I said, it’s not as if Tatami’s hideous or anything. I mean, she can be quite charming. Cute in her own way. And funny. But, she’s not quite my cup of tea and, well, it never even occurred to me to . . .”

“Never?”

“C'mon, Shinobu. I think you know me better than that.”

“I suppose I do. So, what gave her the impression that . . .”

“I don’t know!”

“You wrote her a letter, right?”

“Right.”

“And?”

“And, nothing.”

“What did you write?”

“Beats me. It was well over a month ago. But, you can be damned sure I didn’t tell her I loved her.”

“Did you tell her you liked her?”

“In the letter?”

“Yes, in the letter.”

“I don't know. Maybe.”

“Maybe?”

“Yeah, maybe, indirectly. But, so what?”

“Well, there you go, Peador.”

“There I go what? I like this Caesar salad, but good as it is, I’m not gonna exchange wedding vows with it.”

“Peador. You write a letter to a girl you’ve only just met. You tell her you like her. What do you expect?”

“That this isn’t junior high school. That I can tell a woman I find her interesting and want to become friends and it not being big deal is what.”

“Have you considered that Tatami may never have had a boyfriend?”

“She’s thirty years old, for chrissakes.”

“She’s an o-jô-san, Peador. For all you know, she might still be . . .” She looks around the restaurant to check if anyone is listening, then whispers: “She might still be a virgin.”

“A virgin?!?!”

Now, everyone definitely is listening.

“Yes, a virgin, Peador,” Shinobu says in a hushed voice.

I can’t believe what I’m hearing. I’m utterly speechless. I open my bag, pull my day planner out and check the year embossed on the cover. Just as I suspected, 1993. I spin my day planner around to show Shinobu.

“It could be 2013, Peador, but a family like hers would still be old fashioned.”

“Good God, where’s the fun in that? You know, when I heard her father was a university professor, I just assumed he’d be this laid-back hippy. A jungle of Maui-wowie growing in the garden.”

“Which university?”

“Kyûdai.”

“That explains it then.”

“How do you figure?”

“Well, first of all, Kyûshû-danji . . .”

“Sorry?”

“A man from Kyûshû.”

“Ooh, new word! Let me write that down. Kyûshû dango?”

“No! Not dango . . .!”

“I know, I know. I'm joking.” Dango means “dumpling”. “Kyûshû-danji.”

“Kyûshû-danji are notoriously conservative. But, rich and a Kyûdai professor, to boot?”

“To boot? You picked that up in England, didn't you?” She flashes me a self-satisfied smile. “Well, I guess that makes sense in a nonsensical sort of way. I’m telling you, this Tatami’s a real piece of work. I mean, she just flipped out when I told her I wanted to meet her father.”

“You what?”

“I told Tatami I wanted to meet her father.”

“Baka! You know, you’re an intelligent man, Peador, but sometimes, sometimes you can be really, really stupid.”

“W-w-what?”

“One, you don’t tell a girl you’re dating . . .”

“We aren’t dating.”

“Whatever. You don’t tell a girl that you want to meet her father. That, that’s practically the same thing as proposing to her. Bakamé!”

Good Lord.

“Why, Peador? Why on earth would you ever tell her that?”

I’ve always harbored the suspicion that coming to Japan was a mistake. But, desperation rising from a dearth of viable options, coupled with morbid curiosity, silenced the doubts long enough for me to jump on board without considering where the train would take me. And, once in Japan, despite the frustrations and the alarming conviction that my life was now way off track, inertia alone kept me barreling ahead on a collision course with Mie who would eventually derail me. Why did I tell Tatami I wanted to meet her father? “He's a professor of architecture is why.”

“Oh,” she says, confronting the method to my madness. “You haven’t given up, have you?”

“Of course not. Why the fuck would I?”

“It’s just that . . .”

“It’s just what?”

“You’re such a good teacher. Everyone says . . .”

“Ah, Jesus Christ, Shinobu! You can’t imagine what an insult it is for me to hear that.”

“Gomen. Hontôni gomen.”

“Oh, don’t apologize. Maybe, you’re right. Maybe I am a good teacher, but . . . but, God, every time someone tells me that, I can’t help but feel like a complete loser.”

“I haven’t heard you talk about it, so I just assumed you’d . . .”

“I’ve been a bit preoccupied.”

“Only a bit?”

“Obsessed, I know. And, I’m sorry. Gomen ne.” No one understands this better than dear old Shinobu; it’s on her damp shoulder that I often cried, so to speak.

Thanks to Mie dumping me, I was a basket case the first half of the year this year. It wasn’t until my birthday last month that it finally dawned on me how much time had been wasted. You can’t go back and recoup a loss of time like you can with, say, money. You can’t retrace your steps like you do to recover a misplaced wallet, can’t go to the neighborhood kôban, fill out a police form and hope some Good Samaritan will find it for you. No, time moves with relentless abandon forward, each day giving up the ghost at midnight, never to be resurrected again. What is lost can never be recovered. All that remains of those twenty-four hours is a haunting memory that, if lucky, will terrify you into trying to make the most of the days yet to come.

When I found out that Tatami’s father was a professor of architecture at supposedly the best university in the region, naturally I was keen to meet the man. Here’s a chance to get back on track, I thought, a chance to get into some kind of research program at the university, to study more about architecture, hell, maybe even intern with a firm, get my hands dirty working part-time as a carpenter, anything to make my stint in Japan meaningfu

l. It hadn’t occurred to me that Tatami would end up misinterpreting everything I would do or say in the context of love.

“I’ve really stepped in it this time,” I tell Shinobu.

“It sounds that way.”

“It gets worse,” I say. “As much as I would still like to meet her father, I’ve tried to put some distance between us lately.”

“That’s smart.”

“You’d think so, wouldn’t you, but now I can’t get rid of her. Tatami’s constantly slipping these dainty letters and rice balls in my mailbox, and I swear everywhere I go, she just magically appears.”

“No!”

“I’m not kidding, Shinobu. I go jogging around Ôhori Park and there she is sitting on a bench with her parasol, smiling and waving at me each time I pass. I go to the beach to play volleyball with some guys and as I’m about to serve there she is again strolling on the boardwalk with that damned parasol and a dress right out of the Victorian era.”

“Peador, I, um, I hope you don't mind my suggesting this, but why don’t you just go back to America?”

“I’d love to, but . . .”

But what is there to go back to? My predicament is, as vexingly clear as always, money. Money, that is, the persistent and pernicious lack thereof which very nearly kept me from graduating university. Were it not for the generosity of my university extending me loans in the form of IOUs, I would never have completed my final year. Unfortunately, these very same IOUs have become a ransom of sorts, keeping my transcripts hostage, bound and gagged, in the registrar’s office, and preventing my application to graduate school.

Credit must also be given to George H.W. Bush. Though he put in a stellar performance bombing the bejeezus out of uppity Darkies, his song and dance routine about the economy getting better was less convincing. “Staying the course” with the Voodoo Economics meant there weren’t many entry-level jobs available for new graduates when I finished school.

None of my friends, including the more talented, well educated of the bunch, had anything resembling careers. We were called Generation X'ers or slackers as if the employment disappearing act had been our own fault. But let me tell you, during the recession, dare I call it a depression, my BS in Architecture was what Vonnegut might call “ornamental” in a country that had stopped building.

My parents with their “just go down the street and apply for a job at McDonald’s” attitude were no help, either. If anything, they fueled my desperation. They were mad to think I would ever be able to pay off all that debt by standing behind a counter and saying, "Would you like fries with that, sir?"

So, it was in search of much greener pastures that I packed my bags and came to this country. It was boom time in the Land of the Rising Sun, and the Japanese were buying up America as quickly as the U.S. could pawn itself.

I had a simple plan with modest goals: stay for a year or two, pay off the university debt, do some research on Japanese architecture, master the language, and, what the hell, fool around with the geishas. Then, with my pockets full of yen, I would head back to the States, go to graduate school and have an illustrious and well-compensated future. Sixteen months later, where am I? Broken hearted, speaking broken Japanese, and as broke as fucking ever.

“I’d love to go back, Shinobu, but even with this new guy, Clinton, I don't know. The economy’s still . . .”

“The economy’s bad here, too.”

“So, everyone tells me, but I’ve got a job that pays scandalously well considering how little I work.”

At a time when most of my friends back home think that going from manning the cash register at a Starbucks to being the barista is a career move, that is saying a lot.

A friend in Portland sent me a depressing letter a few months ago. He'd been beat into such abject submission by the lack of opportunities in his field of design that he was now gleefully chasing after a miserable little carrot: the benefits package managers at Starbucks enjoyed.

“Whaddaya think,” his letter asked. “Better pack your bags and come to Japan,” I wrote back.

“Well, whatever you do,” Shinobu said after some thought, “don’t sleep with Tatami.”

The waitress comes to remove our plates once we’ve finished. She asks my friend whether she’d like aisu kôhi or hotto. Shinobu says she’ll have the iced coffee, I order a cup of the hot.

“You mind if I smoke?” I ask.

She doesn’t, so I light up.

“Mild Sevens?” Shinobu says, noticing I've changed brands.

“I've given up Hope.”

The waitress brings our kôhi along with a ceramic bowl filled with small plastic containers of non-dairy creamer. Knowing how much I hate the crap, Shinobu asks if they have fresh cream. They do. And, when it’s brought to our table she takes my cup, adds two and a half spoons of sugar and the cream, then stirs it with an economy of movement evocative of the tea ceremony.

“Arigatô, Shinobu.”

After almost a year and half, Shinobu knows most of my fussy quirks, knows how sullen and difficult I can be at the best of times, but still she dotes on me. If only I were attracted to her. If only I could look into those forlorn eyes of hers and feel what I once felt when I looked into Mie’s, I'd probably get down on my knees and propose to Shinobu on the spot. But, I don’t. And so, like a divining rod seeking water, my gaze returns to the beautiful women flitting by like exotic butterflies outside the window.

Just then a peach-faced New Zealander by the name of MacDoogle passes. He walks on the tips of his toes, the heels barely gracing the asphalt, as if his weight were being aided by cherubim.

“Aitsu s’kan,” I grumble, snubbing out my half-smoked cigarette. I can’t stand that guy. “M’neem’s Pollyenna. I love ay-vry-thing end ay-vry-one end ey-vry-weer in Japayn. Lah dee dah! Lah dee dah! Fucking Kiwi!"

“His name’s Pollyanna?”

“No, his name’s MacDoogle. Can’t remember his first name, but, if I’m not mistaken, I think it was Shithead.”

“You’re terrible, Peador.”

“I am. I am. So, I am.”

I’d been having a bad day, at the end of a very bad week in the middle of another bad month when I first met Shithead MacDoogle. So, when I listened to him speak so glowingly of Japan, I just snapped. I couldn’t help but take it as a blasphemous attack on my zealous discontent. I damn near crucified the guy. Not surprisingly, whenever we pass each other on the street now, he ignores me, acts as if I’m not even there. Who could blame him? Seeing Shithead skip by, the stupid smile on his face as always, I now realize the only reason I’ve hated him so is that I envy him his contentedness.

“Have you been able to make any friends?” Shinobu asks.

“Not really. It's hard, really hard, to get to know people here. Japanese or gaijin.”

“It’s difficult for Japanese, too.”

“I mean, I know faces, even know some names that go with those faces, but I don’t really know anyone.”

Four months. I’ve been in Fukuoka for four months and the only person I could possibly consider a friend, Alex, doesn’t even live here. If it weren’t for the crazy Russian blowing unexpectedly into town every now and then from Tôkyô, I’d surely go mad.

4

I was dead tired as I walked home from work last Thursday. I’d woken up in the middle of the night so that I could go to the Yamakasa, a festival in which teams of bare-arsed men schlepp one-ton mikoshi shrines around the old town. All I wanted to do was collapse on my futon and sleep, sleep, sleep.

Hearing a low rumble of a testosterone-fueled engine, I turned around to find Alex riding an old chopper and wearing a Nazi Schutztaffel helmet.

"Sieg Heil, mein Freund,” he said. “Let’s go drinking?”

How could I say no?

Later, Alex’s friend, Nobu, drove the three of us in a rust bucket of a station wagon to a small bar in Nakasu called Anchor. The bar was located on a squalid back street in a building packed like a broiler house with s

mall bars. I expected Anchor to be a typical dive with the usual contingent of the gaudily dressed, outrageously coifed hostesses pumping water into the whiskey, and drunk salarymen belting out maudlin enka songs. Boy, was I ever wrong.

Stepping into Anchor from the dimly lit corridor I felt as if I’d been transported fifty years back in time to the bridge of a Pacific War era battle ship. Behind the counter, Anchor's master was dressed like an admiral, straight as a ramrod and decked out in a crisp white Imperial Naval officer's uniform. As we entered, he removed a silver whistle tucked into his breast pocket and blew with ceremonial flare announcing our coming on board.

Most of the customers were gravely serious, more like right-wingers or yakuza types than salarymen. There wasn't a woman in the bar, or a hostess, for that matter. The karaoke system crackled with rousing martial songs, accompanied by a video highlighting Japan's military prowess. Had I mistakenly stumbled into the bar on my own, I would have made a quick about-face and retreated, but Alex and Nobu seemed to be regulars. The Admiral directed the three of us to the counter.

After we’d polished off a large bottle of shôchû, the Admiral came from behind the counter and led me to a clothes rack filled with old military uniforms. He pulled one of the uniforms off the rack, then helped me into it. Brown overalls, a flak jacket and leather pilot’s cap complete with goggles. As a finishing touch, he wrapped a long white silk scarf around my neck, and with a burnt cork added a Red Baron mustache to my face. He then lowered a backdrop showing the deck of an aircraft carrier with a Zero fighter ready to take off.

“Hai, cheezu,” the Admiral said, aiming a Polaroid camera at me.

“Cheese,” I said, trying my best to look like a dead serious kamikaze pilot. Ah, if only my parents could have seen me!

After the shenanigans at Anchor, Nobu led us from one small hostess bar to the next, where we’d drink whisky and water and pick up a hostess coming off work before moving on to the next bar. Before long, the three of us were completely drunk, each of us with a girl hanging on our arm.

Though in recent weeks I’d been relegated to the dating world's equivalent of fetching Gatorade and sunflower seeds for more talented players, I managed to end up with the youngest and prettiest of the tag-along hostesses, sitting on my lap as we drove back to Nobu’s house deep in the woods of Nishi Kôen (Nishi Park). Alex and Nobu went upstairs with their women, leaving the girl and me downstairs in the guest room.

A Woman's Nails

A Woman's Nails