- Home

- Aonghas Crowe

A Woman's Nails Page 9

A Woman's Nails Read online

Page 9

C'mon, Mie. Where the devil are you?

Fifteen minutes is nothing, though, considering I've already been waiting a half a year for her. Six long, lonely months. I never gave up hope. Doubt may have gnawed that hope to shreds, but I haven't given it up.

You'd think I'd know what I would want to say to Mie after having waited so long to see her again, but I don't. What will she say to me? And how will she act? What are the odds of my getting her back? Do I even want her back after all this time? Now that I am finally here, it occurs to me that I never considered that. It has been too far beyond my limited imagination since she left me to think of the break up as anything other than my having been robbed of a profound and rightly deserved happiness. If only my future self would journey back to this present moment and tell me to open my eyes and take in all the beautiful women passing by, and, with a gentle elbow to my ribs, convince me of the very thing that has been nagging at me since my move: that, maybe, just maybe, I am better off without Mie, and that, starting at this very moment I should take the first step towards moving on with my life by standing the bitch up. Should the future me indeed pay myself a visit, I seriously doubt if I would be very convincing. Again, I'm not much of a salesman.

I step inside Mister Donut to get out of the chill, and am greeted by a cloyingly aromatic mélange of the “world's best coffee,” month old frying oil, and cigarette smoke. Through the unhealthy miasma a small table in the furthest corner comes into view. It’s the very same table at which Mie and I waited out a sudden downpour on Father's Day last year. Though the donut shop is hopping, “our table” remains empty, as if it's been reserved for us.

I want to take my place at the table and relive that day, to hold Mie's hand as I did then and talk to her about moving to Portland with me. I long to hear the words she spoke to me that rainy afternoon, that there was nothing more in this world she wanted than to live with me in America.

Mie had left her boyfriend for me the night before and was now mine--my girlfriend, my lover. And, looking into her warm brown eyes I thought I knew who the mother of my children was destined to be. Mie was mine, and as the rain poured heavily outside I couldn't begin to imagine that I would ever feel as forlorn, confused, or as bitter as I have been all these months. It was inconceivable that the happiness I was feeling then would be so ephemeral or that four short months later the only thing that would sustain me through the autumn and winter would be the emaciated hope languishing within this miserable heart of mine, the hope that the red string tying us together and which had helped me find Mie was merely frayed, not broken.

3

“O-Kyaku-sama. Anô . . . O-Kyaku-sama,” a young woman behind the counter calls out to me.

“Hai?”

“Gochûmon okimari deshôka?”

Have I decided what to order? I tell her I'm waiting for someone and she makes a slight bow.

When I turn around and look towards the entrance I notice Mie standing on the sidewalk just outside the entrance of Mister Donut. She hasn't seen me yet, so I wait a moment before exiting. She is as beautiful as I've remembered her, painfully so, and every little thing I adored about her rushes back to me, that tsunami of memories washing over me again.

How on earth did I ever expect to move on, let alone fall in love with someone else, when that woman, that unforgettable woman standing there, was the one who had broken my heart?

I have to suppress the urge to run outside and hold onto her so tightly that she'll never be able to leave me again. Taking a deep breath, I take a step towards the automatic doors. As they open I softly call out her name, “Mie-chan.”

She doesn't hear me. My heart is in my throat, pounding away madly, stifling any sound. I could almost cry.

“Mie-chan.”

She turns towards me and says, “Oh-chan.”

It’s been months since anyone called me Oh-chan. Tears threaten to well up in my eyes. I take a step towards her, my hand extended. She takes it, the touch warm, familiar and comforting. It’s as if I had been holding it all this time.

“Hisashiburi ne,” I say. It’s been a long time, hasn't it.

“Ne.” She looks me as if to take an inventory of this former lover of hers. “You've lost weight, haven't you?”

It's not the only thing I've lost, Mie-chan.

“And, you've gone and cut you're hair, too. It's so much nicer when it's longer, Oh-chan. It's so . . . “

“Messy, I know.”

“No, no. It was curly . . . Adorable. I really liked it long.”

I want to hold her and kiss her and tell her how much love her, how much I've missed her, how much . . . But before I have the chance, she turns to beckon a young woman over.

“I've, um, invited a friend along. Yuki-chan. We work together. I guess I should have told you, but, well, she wanted to meet you.”

“Meet me?”

This Yuki-chan skips over to us, a bright smile on her pretty face.

“Hajimemashite,” I say to her with a slight bow.

“Wow!” she says. “You’re Japanese is really good.”

After introducing us quickly, Mie says, “Ikimashôka,” so we take off down the street past the cute CABIN cigarette campaign girl, the warabi mochi vendor who's now standing behind his pick-up serving a customer, and an Israeli selling cheap jewelry and other tchotchke on the sidewalk. The Israeli nods at me, and Mie's co-worker asks if he's my friend. I reply that I've never seen him before in my life, which the girl finds enormously funny. It keeps her tittering for a while just as it had done to Mie a year ago.

Mie leads us through a cracked tinted glass door into a well-known bar on the first floor of a run-down karaoke building called the Big Apple where the cheap beer and even cheaper women attract South American men and boys up from the Navy base in Sasebo like flies to warm shit.

We sit under a canopy of black lights and neon beer signs on precariously high stools around a narrow table that wobbles. Yuki is wide-eyed and bubbling over with childish excitement. She says she's never been to a gaijin bar and asks if I come here a lot. This is precisely what I'd like to ask of Mie because the thought of her hanging out at grotty gaijin bars like this all these months since she dumped me is disturbing.

“No, I've never been here before,” I reply. While it is a relief to learn that Mie, too, is a virgin of sorts, the unsettlingly vivid image of her hanging out here and flirting with men, particularly other foreign men, is now seared into my mind. I've never been the jealous type; this is a new emotion for me.

“It's just like America,” Yuki says earnestly, compelling me to ask her whether she's been. “Me? No, never. I haven't even been to Tôkyô.”

“Yuki wants to go to America,” Mie informs me. “I told her she should go to Portland.”

“I wanna go, wanna go, wanna go!” Yuki cries. The girl wants to go so badly she can barely contain herself.

Mie asks if I've been home since . . . since, well, you-know-when . . . since we last met.

“To Portland? Nah, not yet.”

“No? I'm surprised to hear that.”

Me, too. Time flies when you're having fun. “It's been over a year now. Thirteen months.”

“Eh? Thirteen months? Aren't you homesick?” Yuki asks.

“Sometimes, yes . . . But, not right now.”

“Ne, have you got a girlfriend,” Yuki says.

The question was bound to come up sooner or later, but now that it has I don't know how to reply with Mie sitting next to me. When I hesitate to answer, Mie tells her, “Oh-chan says he doesn't have a girlfriend, but I don't believe him.”

“No way!” Yuki says.

Whatever.

Yuki, I'm now told, doesn't have a boyfriend, either, obliging me to register similar disbelief at the revelation. “Unbelievable! Yuki, you're much too cute to not have a boyfriend.”

I do try to be polite.

Yuki then says something that surprises me: there aren't enough men in Fukuoka. And as if to

refute any doubt she supports this dubious claim with statistics: “You know there is only one man for every eight women in this city? Maybe I should move to Tôkyô.”

Hearing this from someone as adorable as this Yuki here ought to be like music to my ears, but to be honest, all I really care to listen to is that sweet old melody sung once more from Mie's soft lips that dear old Tetsu is no longer a leading character in her life pageant. Unfortunately, Mie seems to have lost her voice.

I take my box of Hope cigarettes and Mie's Zippo lighter out of my pocket, remove a cigarette and light up.

“Ah, I was wondering where that went,” Mie says of the lighter.

“You left it behind,” I say handing it to her.

“Is it really okay?”

“Of course, it is yours, after all.”

“Yeah, I guess it is, isn't it. Thanks.”

“Don't mention it.”

Mie removes a pack of Mild Sevens from her handbag, lights up, and before the two of us can become pensive, Yuki bails us out of the sinking mood by suggesting we order something to drink. Mie says she'll get it and stands up leaving me alone with Yuki.

The girl is still somewhat gaijin struck, giggling like a teenager whenever I look at her. I don't know why it is, but some Japanese just can't help themselves when they meet foreigners. Given half a chance, they'll rattle off an arbitrarily arranged list of silly questions, which form a hurdle you're obliged to clear before something resembling a true conversation can take place. And so while Mie is away fetching the drinks, Yuki asks whether I like sushi or those god-awful fermented soybeans called nattô that smell like old gym socks. She wants know whether I can use o-hashi (chopsticks) or read the hiragana script, and so on until Mie rescues me with a Corona.

Mie shows Yuki what to do with the wedge of lime, then we clink the necks of the bottles together. “Kampai!”

“Natsukashii ne,” Mie says, alluding nostalgically to the times we drank it at her apartment last summer.

“Ne,” I say. Just looking at the slim clear bottle stirs up so many fond memories. The weekends spent with Mie in Fukuoka, the drives to the beach, the evenings drinking in her apartment, the wild drunken sex all night and the mornings nursing our hangover with Pocari Sweat only to do it all over again until Tuesday mornings when it was back to work in godforsaken Kitakyûshû. “Natsukashii ne.”

Yuki asks me why I came to Japan, another standard question people here are always itching to put to me. The Japanese seem to like simple, predictable and preferably concise answers when engaging someone in small talk, communicating abstract ideas or revealing things too personal doesn't quite go down well, so I brush the question courteously aside, “It's a long story.”

“I'd like to hear it,” Yuki says. “Tell me, tell me, tell me!”

“Me, too,” says Mie.

It occurs to me only now that Mie never knew why I came to or what I wanted to do once here in Japan. Oh, I'm sure I must have tried to explain, but a year ago my Japanese was an embarrassment. To her, I must have appeared little more than a shiftless, albeit romantic, wanderer. How different I must have been from her Tetsu who had become a policeman, because, well, his father and grandfather and, who knows, maybe even his great grandfather had also been policemen. If Tetsu’s father had jumped off a bridge, I wonder if he would have taken a swan dive off it, as well? When I had asked Mie, somewhat rudely I later regretted, why on earth she had ever been interested in marrying a cop, she replied matter-of-factly: for stability. Mie often did that to me, offered an answer that would just stop me in my tracks. What about love and romance, inspiration, or even fate, I protested. In this economy, she explained, those are luxuries a woman can't afford, she replied. Once, when I learned that Mie's mother had had her learn the piano and cello as I child, I asked her if she would do the same with her own children. Of course, she would. For shitsuke, she added, and started thumbing through a tattered Japanese-English dictionary.

“For aesthetic pleasure,” I wondered out loud. “In order to develop a deep and long-lasting love of music?” Nah, don't be so naïve, Peador. Finding the word in the dictionary, Mie handed it to me and pointed at the entry: shitsuke, I discovered, meant “discipline.”

As much as I loved Mie, as painful as her absence has been, it's hard to continue denying what I had already realized but had difficulty accepting: the uncomfortable fact that I never really knew Mie and Mie knew even less about me.

So, I have to go into the long and tired tale of how Peador had wanted to be an architect and designer, but after finishing university, didn't have the means to continue onto a master's program thanks to a mountain of student loan debt accruing at ten percent and unsupportive parents who believed the school of hard knocks would make their son a stronger person despite his pleading that he it wasn't strong that he wanted to be, it was employable. The reason I came to Japan, I then tell my small but captivated audience, was two-fold, that is if you exclude the burning desire to escape from my family and America: to save money for graduate school and, if possible, learn more about Japanese design and architecture. “You know, niseki icchô,” I say in conclusion.

“Huh?”

“Niseki icchô,” I say again and pantomime throwing an invisible rock at two imaginary birds until I realize that what I'm actually saying is “two stones, one bird” rather than “two birds with one stone.” Though this may be a far more accurate description of my experience in this country so far, isn't quite what I meant to convey, so I correct myself: “Isseki nichô.”

Yuki praises my Japanese, exclaiming how jôzu! it is, but, to be honest, I think she's just dickin’ with me. Mie says she had no idea.

“The problem is, though, my train kind of . . . derailed, if you will. I wasn't able to do any of the things I expected to do during my first year here.”

“Ôen suru ken,” they reply, telling me they'll be rooting for me, so I should “ganbatte!” I shouldn't give up. I assure them that I don't give up easily. I wouldn’t still be here today if I did.

4

After drinking the bar dry of Coronas the three of us switch to whiskey and waters. I know I'm going to regret it tomorrow morning, but I'm still hoping for a repeat performance of that first night ever with Mie, hoping that even if words fail me, then perhaps alcohol will succeed as it has in the past in loosening this ex-girlfriend of mine up.

It is unfortunately obvious, though, that Mie has her own ideas of how she'd like the evening to end. She never gets very personal, never lets on to what is happening in her life, whether she is still with Tetsu. Not once does she even drop a hint about our common past. Instead, Mie tries her best to sell me on this co-worker of hers, and even informs me that Yuki has an apartment of her own, a nice place not far from Tenjin, that I ought to visit.

Yuki seconds this. “Yes, yes. By all means, do come over anytime.” She writes her phone number on the back of a business card, and after making me promise to call her, excuses herself to stagger off to the restroom. Mie and I are alone for the first time all evening.

“I think Yuki likes you.”

“Humph, that's nice to know.”

It's hard to hide my lack of enthusiasm. I mean, sweet as the girl is, she just isn't Mie. She can't even begin to compare; this ex-girlfriend of mine set the bar too goddamn high.

“She your type?”

“My type?” I'm almost drunk enough that I could smack Mie for asking. “I think you already have an idea what my type is like.”

“She's a good person. I think she'd make a nice girlfriend for you.”

“Do you now?”

“Yes, I do. I really do think you'd make a nice couple.”

“You really believe that's why I wanted to see you tonight? So I could meet someone new?”

“It's just . . . You sounded so . . . I don't know . . . so sad and lonely over the phone.”

“I was . . . I still am sad and lonely, Mie-chan. But dating someone like your Yuki isn't going to help me

in that department.”

“Why not?”

“Why not? What are you, stupid?” I drink the rest of my whiskey quickly. Some of it trickles out of the corner of the glass, runs down my chin and neck. I grab her hand which she's done a fabulous job of keeping out of my reach and taking a deep breath to keep myself from exploding, begin, “I'm sorry, Mie. It's been a long, long, long fucking time since we last met. I don't know how you've spent the last six months, but, let me tell you, I've thought about you each and every day since you left me. And as sad and lonely as I've been, I've managed to carry this foolish hope in my heart that maybe, just maybe if I became a better person or if circumstances changed, if fortune deigned to smile rather than shit upon me for once, then you and I could be together again and everything would be okay. And here we are finally together again and you can't wait to pawn me off on someone else.”

“That wasn't my intention.”

“You know what your friend Yuki is?”

“No, what?”

“She's a consolation prize. She's a consolation prize when I want you, you, you, and no one but you so badly I can barely look at another woman without being reminded of how much I miss you.”

“I feel sorry for you.”

Yuki returns finding me with Mie's cold, dead fish of a hand in mine and scolds us for cheating, “Uwaki-wa dah-mé!” On whom Mie and I are supposedly cheating Yuki doesn't say. But, Mie takes it as a hint to stand up and give Yuki the seat next to me. Yuki sits then takes my hand and asks me if I like her, “Yuki-chan no koto suki?”

I smile sadly because it reminds me of the very words Mie spoke to me on the floor of her bedroom that first night nearly a year ago when we'd drunk ourselves silly on saké. “I love you. I love you so much I could cry,” I say to Mie, but it's Yuki who hugs me and kisses me and tells me she loves me, too.

The past has been waiting for its cue to burst in through the tinted glass door of the Big Apple and spoil our reunion. I ought to give Mie credit for having known this and tried in her own way to keep the past as far away from the present as possible by carrying on as if our common tragic history no longer had anything to do with us today. But it was an effort that had been doomed to failure when she had extended the invitation over the phone. I am my past, the sum of my disappointments and failures.

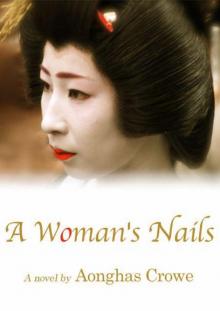

A Woman's Nails

A Woman's Nails